KORO (pronounced /ˌkɔːrɔ/, echoing the Greek choros [χορος], meaning “space” or “dance”) is a programming language designed to express human movements through a syntax inspired by LOGO, a classic geometric language developed in the 1960s by Seymour Papert. LOGO’s revolutionary vision was to make programming intuitive and accessible—even for young learners—by simplifying the domain to visual tasks like painting and using a syntax that mirrors natural language.

KORO extends this philosophy to the realm of human movement, dance, and choreography. It offers a simple yet powerful programming language tailored to a specific domain: the dynamic interplay of body, space, and rhythm. The language retains a structure that closely aligns with natural language, enabling users to articulate movements in a way that feels clear and intuitive. By providing an expressive and executable dance notation, KORO bridges the gap between bodily intuition and algorithmic precision.

Through abstraction — defining, naming, and nesting timed actions — KORO empowers creators to build and notate complex choreographic sequences. Starting from the most fundamental actions — positioning and rotating limbs, adjusting weight distribution, reorienting the body and aligning the head, spine, and hips — the language allows for the construction of synchronized patterns, couple and group formations, and evolving collective shapes. All visualized with real 3D figures in real time.

This document begins by introducing the Core Concepts of KORO. Unlike LOGO, which focuses on the movement of a turtle (as a painter abstraction), KORO is designed to model timed human movement. Its key innovation lies in the integration of timing — a critical element e.g. in dance and choreography — as a foundational feature of the language, enabling precise synchronization and temporal control of movements following a given beat, of individual and multiple dancers simultaneously.

Next, it details the Dancer Commands, based on a skeleton model borrowed from the 3D gaming world. The commands include actions such as adjusting body positions, executing gestures, and dynamically grouping or de-grouping dancers to create complex, coordinated sequences. You can also find a comprehensive version of this chapter in the KORO language reference at section 6.

The document then lays out the idea of a Standard Library, which is planned to include pre-defined functions for modeling common dance styles (e.g., Tango, Jive, Salsa, Bachata, Discofox) and their movement patterns. This area is an ongoing work in progress. The initial aim was to develop an algorithm-based visualization system for Rueda de Casino, a spontaneous, group-oriented Salsa style with synchronized movement among multiple dancers.

The language’s potential extends to other disciplines — such as gymnastics, martial arts, and theatrical choreography — each requiring unique modeling and abstraction. The library’s future expansion reflects KORO’s adaptability to diverse timing- and movement-based domains.

The language is part of a long legacy of dance notations and (software) systems, which are discussed in more detail in the References section, describing the individuals, works, and inspirations that shaped KORO’s development. This includes prior art in the areas of dance modelling and dance notations, and other research that informed its design philosophy and technical implementation.

KORO aims to be a fresh, modern, generic, and flexible notation for movement and dance, accessible to all through its Free Software and commons model. You can help achieving its goals. Find out how in the Contributing section.

In KORO, letter casing has no meaning. In the code examples provided throughout this document, all builtin language commands and keywords are in UPPERCASE, whereas everything newly defined (variables, procedures, functions) are displayed in lower case.

...

...

The LOGO interpreter is extended with the concept of timed actions. It already knows the concept of functions and procedures with scopes, which are opened on each new call, e.g. to include local variables.

This concept is supplemented by a new concept of time-controlled (event-controlled) code execution, which on execution will be synchronized to the beats of the music. Timed Handlers have

ON @123,ON statements andAll timed Handlers are synchronized to the music at all abstraction levels (function call depths). Actions will be executed in parallel, e.g. hand and foot movement at the same time, when given the same events (beat timing) with ON:

ON 1 dile·que·no@4 ON 1 clap

This way of describing activity is very close to the way choreographers and dance teachers describe it to their dancers in reality. Everything you specify after ON is executed only when the given trigger event(s) (beats) happens. It is stopped, when the given end trigger (beat) is reached or the surrounding timed function ends.

Timed actions can be sequenced by specifying a consecutive beat timing, e.g. ON 2 and ON 3.

Timed Handlers are created with the ON statement, which must be followed by a condition. It is either:

@1, @2, @3, @4, @5, @6, @7, @8, @1&, @2&, @3&, @4&, @5&, @6&, @7&,

@8&@123, @567, @67, @81, @7812@1357@2;1 (the second 1), @4;48 (the fourth 4 and 8)

Contrary to a function or procedure, a handler declared by ON is cleared as soon as there is nothing more

to process. Every function, every piece of code, even a handler itself, can create further handlers using nested

ON instructions. Handlers therefore form a nested hierarchy. A handler is cleared, when any of the

surrounding timed functions ends. .

A handler is triggered by a time event (a beat or half beat). It can create handlers itself, which can then be

triggered by later time events. The initial triggering time event is a special case. It must be passed on to all

subordinate handlers immediately: If a handler itself defines a handler via ON 1 that must be executed

immediately, the runtime environment must also execute it immediately, as otherwise the event will not be handled.

This is a typical case that may be repeated deep into the handler hierarchy. A good example would be a function that

executes a clap ON 1. If this is scheduled via ON , it must also be triggered immediately

when it is called so that the clap can be heard at all.

As the procedures or functions of Logo, new actions in dancers Logo are defined with the keyword TO:

TO clap ... END TO salsa·step@8 ... END TO dile·que·no@8 ... END

Actions with zero duration can be defined in the classic syntax. If your action has a duration (in beats), you have to specify that duration during the definition, which makes it a timed function. Only inside timed functions you're allowed to use ON statements.

KORO is a case-insensitive language, letter casing has no meaning, and you can freely decide on how to work with the case.

In the LOGO interpreter used, any character not already part of the language (like -,+,*,/,%) is allowed in variable and function names, even emojis like 🤡.

Selecting which dancers should perform given movements is done with the LET (or ASK)

statement:

LET :cantante [

ON @1 [

POINT LEFT·ARM AT { TOP LEVEL 0 CENTER }

]

]

Also, there are builtin groups LEADERS, LEADER and FOLLOWERS, FOLLOWER:

LET LEADERS [ clap ]

LET LEADER [

STEP ...

]

By grouping/coupling dancers, it is also possible to address multiple dancers with one statement.

Dancers can be grouped / coupled and the resulting group object also provides actions and positions to reference.

MAKE "couple GROUP :leader1 :follower2 DEGROUP :couple REMOVE :leader1 FROM :couple ADD :leader2 TO :couple

Another way to use grouping is by creating groups of dancers needed inside dance structures.

; prepare for rueda avenida MAKE "primeros GROUP :leader1 :leader3 MAKE "secundos GROUP :leader2 :leader4

A DANCER is an object that can be created and removed again.

Dancers can be created with the NEW keyword. To ease the formulation of dance specific actions, the

language allows distinguishing between LEADERs and FOLLOWERs:

MAKE "d NEW DANCER MAKE "f NEW FOLLOWER MAKE "l NEW LEADER REMOVE "d REMOVE "f

3D models of the human body exist for decades, and they can be used to describe the rotation and translation of joints with mathematical precision. The “only” unsolved questions are around standardizing a base model:

KORO answers this question by picking up a widespread human skeleton model from the 3D gaming world. In the following chapter, you find commands specific for this model. It has shoulders, all necessary limb joints, a three part spine and fully modeled hands, but only a basic foot model.

For the biological limits there was no reference, so KORO comes with its own values.

When it comes to describing actual movement, how can the description be generic enough to cover people—short and tall, slim and full, etc.—equally, but at the same time be precise enough to represent a choreography?

The approach of only describing the angles of the joints does not fulfill this requirement. The simple imagination, that on one hand, a smaller person dances with a larger person, and on the other two people of the same size dance with each other - and both their movements have to be mapped into a common, transferable code/notation shows the challenge.

KORO has two ways of representing / coding movements. In one case, external references/targets are aimed at and the system takes over the exact alignment of the joints. In the other case, joints can be precisely aligned. The respective use cases will probably only emerge over time.

One way to modify a dancers pos is to position body parts is by pointing them at targets (target positions) with the

POINT ... AT command. This command is executed for every dancer, if not limited by a surrounding LET

statement.

POINT <body part> AT <position>

POINT LEFT·WRIST AT {0, 0.5, 0}

FULL·POINT HEAD AT {EYE LEVEL 1 WEST}@GROUP

POINT BOTH·KNEES AT {KNEE LEVEL 0.2 NORTH}

By using the command FULL.POINT, the operation will affect more than the direct part / joint.

Body parts like arms, legs, and the torso can be addressed, e.g. place the left wrist over the head - and let the arm follow. A special algorithm (inverse kinematics) is used to adapt the joints inside human biological limits to get as close as possible to the target position. The following parts can be pointed to a target:

HEADLEFT·WRISTRIGHT·WRISTLEFT·FOREARMRIGHT·FOREARMLEFT·ARMRIGHT·ARMLEFT·SHOULDERRIGHT·SHOULDERLEFT·ELBOWRIGHT·ELBOWLEFT·LEGRIGHT·LEGLEFT·KNEERIGHT·KNEELEFT·FOOTRIGHT·FOOTLEFT·TOERIGHT·TOEYou may point more than one body part at a time, e.g. place the wrist over the head with the elbow pointing to the front. E.g. FULL.POINT RIGHT.WRIST AT ... will also lean the whole upper body over to reach the given target.

Targets are positioned relative to a reference. The relative new position is specified either in the classic { x z y } or { x y } form or in a more human-readable form of { <height level> LEVEL <distance> <direction>}.

There are different references for classic or human-readable position:

| Reference type | Example |

|---|---|

| Relative to the body part (its joint point) - default | { 1 0 0.5 }@SELF |

| Relative to a dancer (its center axis) | { 1 0 0.5 }@DANCER |

| Relative to a group/couple (its center axis) | { 1 0 0.5 }@GROUP |

| Relative to a global reference (e.g. center of a circle) | { 1, 0, 0.5 }@center |

Global references can be defined as a variable globalref, e.g. globalref center {0, 0}

Classic positions are 2- or 3-element-lists or arrays: { x z y } or { x y }.

| Name | Percentage |

|---|---|

MAX |

150% |

OVERTOP |

125% |

TOP |

100% |

FOREHEAD |

94% |

EYE |

92% |

NOSE |

91% |

MOUTH |

90% |

NECK |

87.5% |

SHOULDER |

85% |

CHEST |

75% |

BELLY |

62.5% |

HIP |

50% |

THIGH |

37.5% |

KNEE |

25% |

FOOT |

5% |

FLOOR |

0% |

The current position in 3 dimensions of a body part of a specific dancer instance can be requested with the

POSITION function. This is useful e.g. in conjunction with the POINT AT or LOOK AT

functions to provide the returned position as a target. There is also the option to get only a single dimension with

XPOSITION, YPOSITION and ZPOSITION.

<limb>? <dimension> OF <dancer> HEAD? POS OF :follower HEAD? XPOSITION OF :cantante NECK? XPOSITION OF :a SPINE1? POSITION OF :b NECK? ROTATION OF :leader SPINE? XPOS OF :leader HEAD? XPOS OF :leader LEFT·WRIST? ROTATION OF :d LEFT·WRIST? XPOS OF :c LEFT·WRIST? POS OF :b HEAD? XPOSITION OF :a

Hands are the most precise and sophisticated parts of the human body. They consist of a lot of joints and allow for

very complex positions. To simplify specifying dance actions, KORO provides quick commands with human-readable hand

poses. The general syntax is FACE <hand(s)> <pose>

FLAT·DOWNFLAT·UPFLAT·SIDEHOOK·DOWNHOOK·UPHOOK·SIDESHAKECROSSEDBURIEDFor more complex hand poses, the same form of targeting as for the main body parts also exists for the many joints of

the hands, using the ROTATE and POINT <finger< AT <position>. Examples:

ROTATE

THUMB[·1,·2,·3]INDEX·FINGER[·1,·2,·3,·4]MIDDLE·FINGER[·1,·2,·3,·4]RING·FINGER[·1,·2,·3,·4]PINKY[·1,·2,·3,·4]As with the spine, where can address the whole spine by using just the SPINE keyword, but also can

address a specific joint of the spine with SPINE[1,2], you can do the same with the fingers. Usually, the

finger joint rotation is evenly spread throughout its joints. Only if you need some rare gestures, you would address

single joints. So use XROTATE LEFT·INDEX·FINGER TO/BY or BEND LEFT·INDEX·FINGER BY/TO to

eventually influence its multiple joints at once. You may also use LEFT·INDEX·FINGER·1? XROTATION OF

:dancer to request the joint (added up) x-rotation of all its joints.

The Feet are not as precisely modelled as the hands. You will not be able to control every toe separately. Instead, the feet are modelled as having a "single" toe, hidden inside a shoe. This is mainly because I based the whole language on the skeleton models present in the gaming world, where you apperently need your hands, but your feet are always hidden in shoes/boots. Which is also the case for typical dancing, yoga, and so on.

The head is pointed to a position with the LOOK AT command. It is the equivalent of POINT:

LOOK AT {EYE LEVEL 1 WEST}

The Spine is modeled having 3 parts which can be rotated independent of each other.

The hips themselves are the centerpiece of the modelled dancer in KORO. If they rotate, the whole model would rotate

with it. In reality, humans are able to rotate their hip indirectly by changing their legs and their spine position.

This is simulated in KORO with the HIPS command.

Although KORO (so far) has no notion of physics and therefore weight, it has a way of placing the body over the left

or right foot or somewhere in between. This simulates the moving of the body weight from one foot to the other, which

is something happening regularly with humans, e.g. during walking, dancing etc. By moving the weight, the overall

position of the dancer may change, as its always right under the hip. The command for modifying the body weight is

WEIGHT

Every body part is connected to the human skeleton via a joint, which can be rotated in up to 3 dimensions. The

rotation can be performed in a more technical way by providing angles for these dimensions. The corresponding command

is ROTATE. There are also commands to change only a single dimension, XROTATE,

YROTATE and ZROTATE.

ROTATE LEFT·WRIST TO {0, 0, 10}

ROTATE HEAD {0, 5, 5}

XROTATE HEAD 5

YROTATE HEAD 5

ZROTATE HEAD 5

Rotating is more helpful with representing hand and head gestures than whole body movements, as the angles differ depending on the height of the dancers, their starting position etc.

There are also more human-readable commands for performing the same tasks:

BEND RIGHT·WRIST 10 TILT LEFT·SHOULDER 20 TURN HEAD 10 RAISE / NOD HEAD 10 BEND LEFT·PINKY 45

Not all rotation dimensions are possible for all body parts. KORO minds the rotational limits of the human body. The following table shows the mimimum and maximum angles for rotation in the three dimensions for every body part. If left blank, the dimension is not available for rotation for the given body part:

| Body Part | X-Rotation XROTATE BEND TILT |

Y-Rotation YROTATE TURN |

Z-Rotation ZROTATE RAISE NOD |

|---|

The rotational limits for the fingers are:

| Finger Part | X-Rotation XROTATE BEND |

Y-Rotation YROTATE TURN |

Z-Rotation ZROTATE RAISE |

|---|

KORO standard library functions use the middle dot (·), e.g. in dile·que·no. The background is that in dancing, moves often have names consisting of multiple words. In programming, these words, when used to name a function, have to be connected somehow. Programmers typically either use an _ (underscore) or just glue the words together, e.g., by using a method called camel case, where every new word starts with an uppercase letter, like in dileQueNo. There are not many other options, as most programming language compilers and interpreters do not support more than the typical ASCII characters. As this is different with the KORO interpreter, we decided to use the middle dot to separate words in naming dancing moves in the standard library. The editor web component we supply for easy programming supports this character directly. In the editor we provide, a middle dot can be created by typing two normal dots (..).

KORO is a free software project rooted in the principles of openness, collaboration, and shared knowledge. This commitment to freedom extends beyond the software itself to the very fabric of its ecosystem, ensuring that creativity and innovation remain accessible to all.

The term "free software" refers to software that respects its users' freedom to:

KOROs source code is freely available for inspection, modification, and redistribution. The KORO Standard Library of moves — a curated collection of dance, gesture, and choreographic primitives — is designed as a shared common. This means it is public, accessible, and open for reuse, adaptation, and extension by anyone. This approach ensures that KORO and its knowledge base are not locked behind proprietary walls but instead serve as a foundation for collective progress.

As a user of KORO, you are empowered to:

However, with this freedom comes with a simple but critical responsibility:

KORO is licensed under the GNU Affero Public License (AGPL), a copyleft license that ensures these freedoms are preserved even in networked environments. Here’s what this means in practice:

If you modify KORO or its libraries and distribute your version, you must make the complete source code of your modifications publicly available to all users of your version.

This applies even to web-based services: If you run KORO as a service (e.g., a choreography platform), users must still be able to access the source code of the software they interact with. The AGPL strikes a balance between protecting user rights and encouraging transparency in collaborative development. By adhering to this license, KORO ensures that no one can privatize or commercialize its ecosystem without contributing back to the community.

By choosing the AGPL, KORO aligns with the broader free software movement’s goal of democratizing technology. This license:

For artists, choreographers, and developers, this means you can build, experiment, and collaborate without fear of exclusion or artificial barriers.

For full details about the GNU Affero Public License, visit the GNU Project’s licensing page.

KORO is a living project, and its evolution depends on the creativity, expertise, and passion of its community. Whether you're a developer, choreographer, dancer, or 3D artist, there are numerous ways to contribute to make KORO more powerful, expressive, and inclusive. This chapter outlines how you can help shape the future of KORO by contributing to its language source code and its move library.

The KORO programming language is designed to be extensible, modular, and beginner-friendly. Your contributions can help improve its core functionality, performance, and usability. Here’s how you can get involved:

By improving the language, you empower artists, educators, and developers to express their ideas more freely. Your code becomes part of a shared toolset for creating in 3D animation and dance.

The KORO Standard Library of moves is a community-driven repository of choreography primitives (dance moves, gestures, and animations). Your contributions here can inspire new forms of expression and make KORO more versatile for diverse use cases.

Through each new contribution from different cultural backgrounds or artistic practices (e.g., hip-hop, flamenco, contemporary dance), KORO better reflects the rich diversity of global dance traditions. Your moves become building blocks for others to remix, adapt, and build upon.

To ensure a welcoming and productive environment for all contributors:

Every contribution — whether a single line of code or a new dance move — helps KORO grow into a tool for everyone. By sharing your skills and creativity, you:

KORO thrives on the energy and imagination of its community. If you’re passionate about programming, dance, or open collaboration, we invite you to become a co-creator of this project. Together, we can redefine what it means to choreograph in code.

KORO is standing on the shoulders of giants.

The primary technical inspiration for this work is mannequin.js, a remarkable open-source project by Pavel Boytchev. It offers a compelling combination of unique features — such as a pose editor, built-in human rotational limits, and forward kinematics — with a fine aesthetic appearance. Alongside it is free software. As described by its author, its main purpose is to support the teaching of 3D programming concepts, and it seems to provide a good foundation for extending into the goals outlined here.

However, mannequin.js is built on a proprietary skeleton model that, while similar to the quasi-standard bone-based human skeleton model common in platforms like mixamo , readyplayer.me and avaturn, has notable limitations.

Specifically, it lacks spine and shoulder movement, making it incompatible with dancing requirements and standard avatar models - mannequin.js poses cannot be directly applied to typical avatars. Additionally, its implementation up to version 5 relied on older JavaScript paradigms that required significant refactoring to modernize.

To address these challenges, I explored potential modifications to mannequin.js but ultimately decided to reimplement to resolve the critical issues with spine and shoulder modeling by adopting the widespread skeleton model.

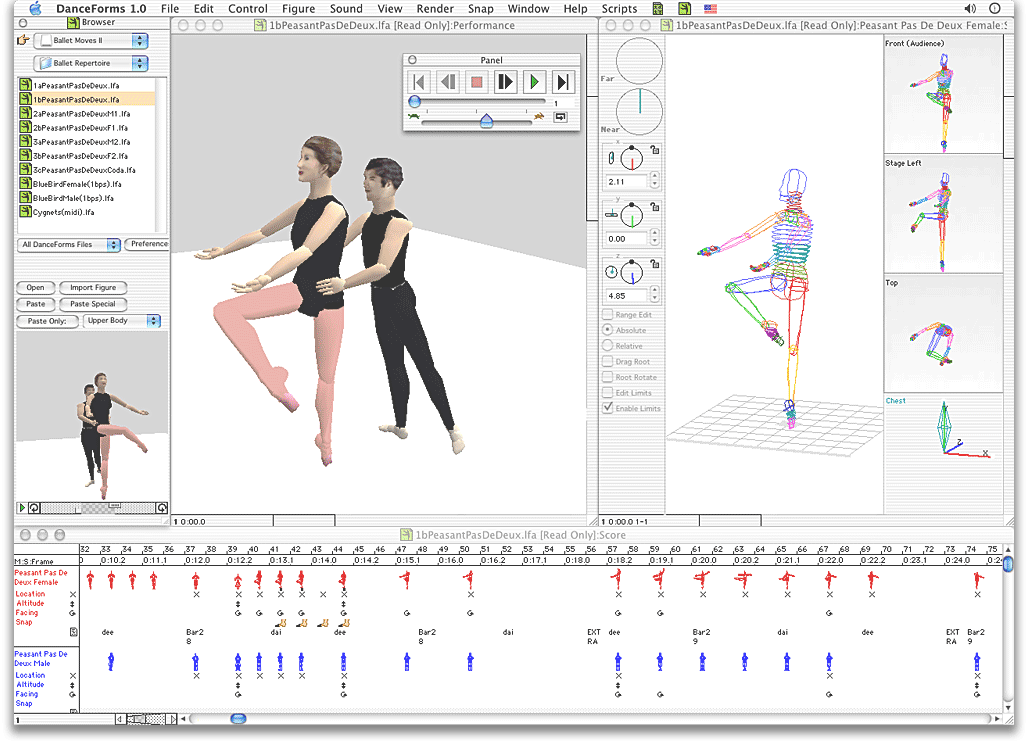

DanceForms is a pioneering choreography software developed by Credo Interactive, originating from the earlier Life Forms software created in the 1980s. Designed specifically for dance educators, choreographers, and students, it offers a 3D environment to visualize and notate movement sequences.

Life Forms was conceived by Thecla Schiphorst, a dancer and software designer, in collaboration with Simon Fraser University professor Tom Calvert. The software allowed users to simulate human movement using 3D models, enabling choreographers to experiment with complex movements without the need for repeated physical rehearsals. Notably, renowned choreographer Merce Cunningham utilized Life Forms to create intricate dance pieces, such as CRWDSPCR (1993), by animating sequences digitally before translating them into live performances.

In the early 2000s, Credo Interactive introduced DanceForms as a more accessible and dance-focused evolution of Life Forms. While Life Forms catered to a broader animation audience, DanceForms was tailored for the dance community, featuring libraries of ballet and modern dance movements, and tools for choreography and notation.

DanceForms provides a suite of tools for choreographers with poseable 3D figures and motion libraries to sketch and animate dance sequences. It has a proprietary score window to chronicle movements step-by-step. It allowed the import of motion capture data.

While DanceForms was widely used for choreographic visualization and education, it has become outdated in the face of newer technologies and software advancements. However, its impact on the integration of technology in dance is significant, having influenced both digital choreography and motion capture applications in the performing arts.

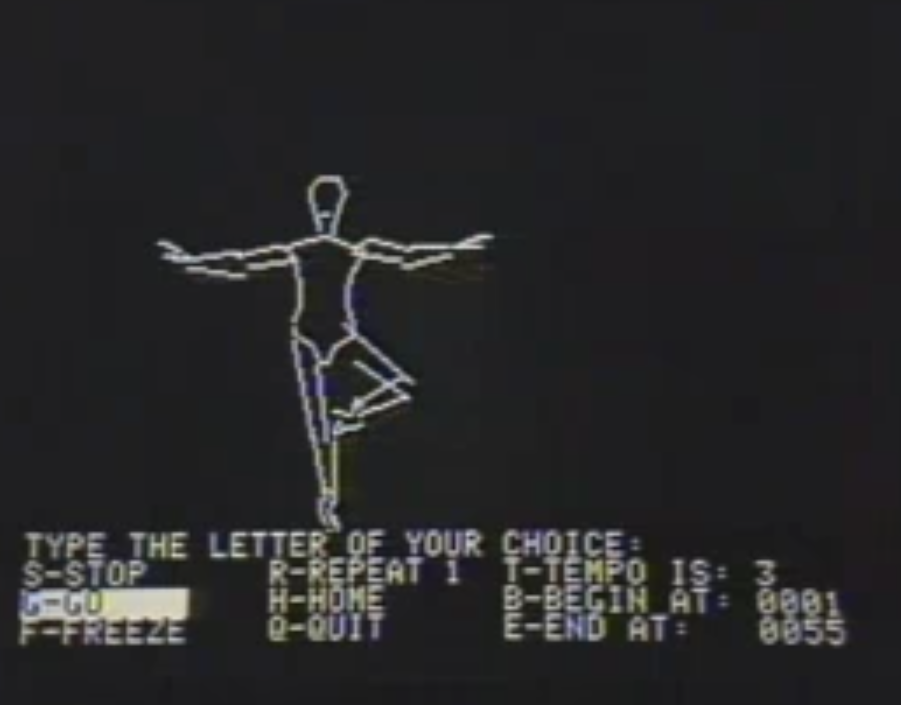

With the dawn of the computer era came new possibilities for graphical visualization of humans and movement, one notable example of a system very close to KORO is DOM, created by Eddie Dombrower, a multidisciplinary artist and game designer with expertise in both dance and mathematics. DOM allowed choreographers to record their work digitally using a simple instruction-based interface, visualizing dance sequences through pixelated on-screen figures. Developed as a closed-source, for-profit product for limited operating systems, it ultimately failed to gain widespread adoption. Technically, it remained more within the realm of notation systems, while the present work introduces presumably the first real programming language for representing dance movement.

| In 2025, Dombrower seems to have revisited his original concept with a modern iteration called FootNotes. |

In 1926, the architect and philosopher Laban introduced a shorthand system for describing human movement in “Choreographie” and developed the concept further in 1928 in the book “Schrifttanz”. This work laid the foundation for his system of Labanotation.

In standard Labanotation, the dancer's body is represented by a vertical system of lines. The center lines describes the central axis of the body, while the lines on the left and right represent the most important parts of the body. The notation is read from bottom to top.

The movement of the legs and feet is recorded within the three central lines, while the movement of the torso, arms, and head is recorded in outer lines. Additional lines can be added to the staff to create more space. Directional symbols indicate forward, backward, left/right sideways, left/right forward diagonal, and left/right backward diagonal. The shading of a direction symbol indicates the level of movement—upwards, downwards, or horizontal. The length of the movement symbols indicates the duration of the respective action; additional character families represent smaller body parts, and additional symbols such as pins and hooks indicate details that change the main action.

Labanotation is still widely used today to encode and preserve choreographic works. See, for example: https://www.dancenotation.org. There are some software solutions, such as those with 3D support, for capturing movement: Labanotator, LabanWriter.

There is even a bridge to robotics.

However, the basic description of Labanotation is not able to describe human body movement in detail and precision due to its inherent fuzziness. There are also no elements of expressing the interaction between dancers.

Since 3D models of the human body exist that can be used to describe the rotation and translation of joints with mathematical precision, Labanotation is a legacy that asks for being transformed into a more modern approach. There is some scientific work in this direction, e.g.

To formalize dance movements and choreographies, numerous other, even older notation systems were developed in the past — nearly all of them predating the computer age.